Nathan Gutman served as a slave laborer for the Nazis during World War II. Liberated by American soldiers at the Mauthausen concentration camp, Nathan described his initial feelings concerning freedom as exhaustion, bewilderment, elation — the realization that terrible war had ended for him. The physical injuries he suffered as a prisoner would heal in time, but the memories of those years always re-visited him.

When Nathan regained strength, he volunteered as part of a Jewish crew on a refurbished WWII American ship the Altalena. Regrettably, the predominant Israeli political faction viewed immigrants and weapons on the ship as a potential challenge to its authority. The newly formed Israeli defense forces fired upon the Altalena setting it ablaze forcing Nathan to abandoned ship and swim to the “Promised Land.”

Once ashore, the problems that Nathan was about to face were like anyone released from prison, managing his days for learning, earning a livelihood and something new — social connections, recreation, selecting housing within his community and an occupation.

Nathan’s immediate task was to become an Israeli citizen. He spoke Polish, Yiddish and, because of his captivity, conversational German. Nathan knew some Hebrew from his rudimentary religious studies, but was far from fluent in the language. Therefore, he enrolled in an ulpan, a crash-course Hebrew language school for Israel’s recent immigrants. After being moved to various labor camps, Nathan had developed mechanical skills. He decided to become a freelance handyman, but also he served in the Israeli Defense Force as an armored personnel carrier (APC) driver. Nathan’s APC was a tracked ambulance with several white patches and a red Stars of David emblazoned on it, the Israeli counterpart of the Red Cross. As a soldier, he saw action in the Sinai Peninsula during the Suez Crisis of 1956.

To succeed in this rapidly growing country, Nathan needed a high school education and then, with luck, credentials for admission to a college, therefore he enrolled in a remedial schooling program while working to support himself. When he was apprehended by the Germans, he was twelve and had only completed an elementary school. The war denied him the opportunity of further studies and even the adolescent pleasures of discovering and dreaming about the opposite sex. Fortunately, through friends, he met a lovely Israeli woman named Zahava. Her name in Hebrew means gold and that was what she was to him. The pleasure of courtship was a delight that he could not have imagined as a slave laborer. They married and, in time, had a family.

Nathan excelled in science and mathematics at school, but he found history boring — and this presented a predicament. The government considered Israeli history the Hebrew Bible, but Nathan was apathetic concerning the Torah’s events and its obscure oddities. He equated this with religious indoctrination, a topic that he perhaps subconsciously resisted because in the slave labor camps that he knew, God seemed absent. This became an insurmountable academic hurdle. Nathan’s grades in all other subjects were excellent, but he repeatedly failed to pass the national history exam in order to receive his high school diploma. Without a high school academic credential, he was ineligible for acceptance at any Israeli university.

Nathan confided his frustrations with the Israeli academic system to a distant American cousin who was visiting Israel. The cousin suggested that if Nathan became proficient in English and was willing to start his college studies pretty much at the beginning, he would help Nathan gain admission to Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg, Virginia. There, Nathan’s lack of a high school diploma would not be a significant issue.

Nathan quickly mastered English and, being a diligent student, he was on track to receive the American mechanical engineering degree in three years — but there was one unexpected problem. The college graduation-regulations stated that all students must pass physical education. As a former slave laborer and Israeli blue-collar worker, Nathan had no time to engage in sports. Now he was told that he had learn to play golf. Since, at that time, there were no golf courses in Israel, Nathan complained that this bureaucratic obstacle was a waste of his time. The only exceptions for this requirement were a physically disability and military veterans who served during a conflict. Nathan then asked if the veteran waiver only applied to veterans of the American armed forces. A careful re-reading of the directive revealed that it was non-specific. Nathan soon presented his advisor several official government documents in Hebrew, along with an English translated version, attesting to his combat service. That June he received his mechanical engineering degree with distinction.

Nathan’s student visa stipulated that he had to return to Israel once he finished his studies. Recent graduates who showed exceptional promise in the sciences however could obtain an eighteen-month extension to gain practical experience in an American company. Nathan was recruited by the research and development department of the Caterpillar Company. His inventiveness impressed his employers and he was offered a job and the promise of an expedited visa so that Nathan could become a permanent resident and in time, a United States citizen. Although his wife and Nathan were loyal Israelis, they accepted the offer and ultimately went on to become productive patriotic Americans as well. Nathan went on to earn a mechanical engineering master’s degree in from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and produced eleven patents, his final job title was manager of manufacturing engineering at Jacobs Vehicle Systems in Bloomfield.

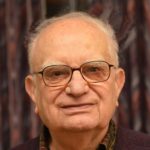

In retirement, Nathan and Zahava settled in Simsbury where he made many friends as a beloved mechanical tinkerer, wood carver, accomplished artist, and extremely creative photographer. Nathan was a student of the technological advances that become available to photographers. He was instrumental in starting of the Simsbury Public Library photography lecture series and served as the club’s coordinator for many years. Nathan took delight in sharing his insight about how the SCC members could achieve a similar result more inexpensively, usually reveled with a characteristic twinkle in his eye. Nathan found ways of using everyday items in new and often surprising ways to create unusual and striking images and was always working on new techniques to try out then pass along to other club members. Nathan’s inspiring story is a tale of many hard-won accomplishments.